How to Edge Out the Competition

- Category:

- Market Information

- Sustainability

What is the capacity of businesses to prosper in a hyper-competitive world? How can they set themselves apart?

Embracing ESG (environmental, social and governance) practices, says Katie Gandy, Business Development Lead for S&P Global’s Sustainable1 business unit. She recognizes this must be in addition to a continued focus on quality, innovation and productivity.

Yesterday (Aug. 22) at Soy Connext in New York City, Gandy reported that in June, global sustainable fund assets hit $2.8 trillion (USD), inching back to the sector record of $3.1 trillion in 2021.

With about half of global food and beverage companies having made commitments to sustainable agriculture in their investor reporting, the focus tends to be on environmental practices, she says.

According to S&P Global, agribusinesses rated material factors ranging from food safety, employment practices and impact on community to customer health and safety, climate transition risk and waste and recycling, plus more. Their Top 5 are:

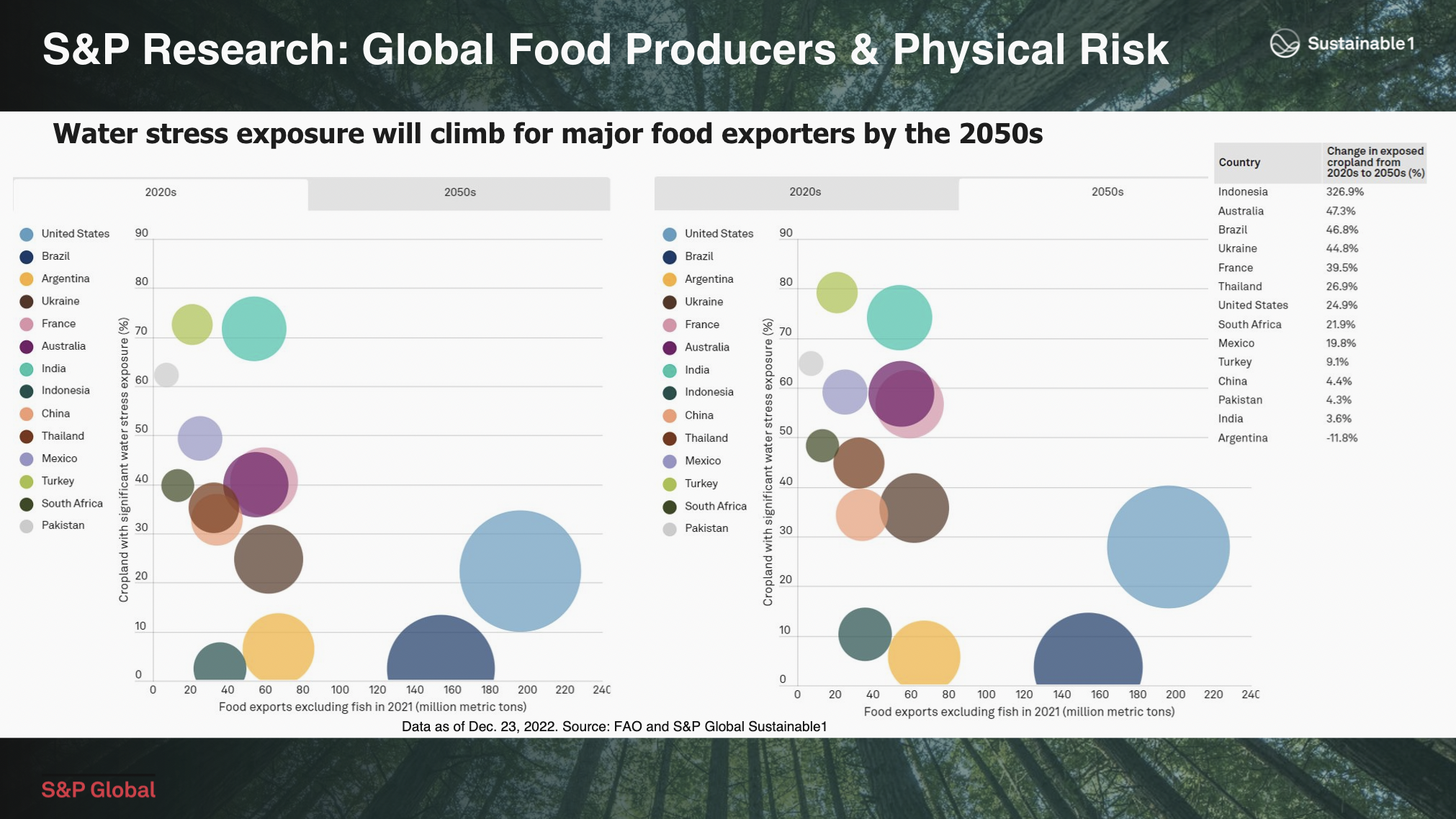

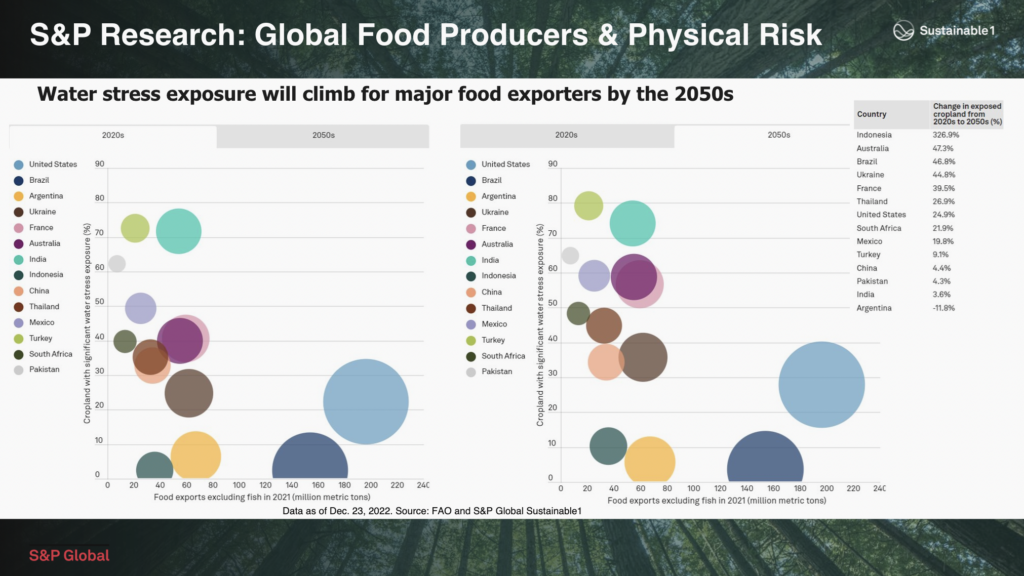

In the category of biodiversity and resource use, data shows that 13 of the 14 largest food exporting countries’ crop land will see increased exposure to water stress by 2050.

In that same time period, the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations estimates food production will need to increase by 60 percent to ensure global food security, and it must do so while conserving and enhancing the natural resource base.

Water is a major input throughout the food ecosystem – from the farm through all the steps in the value chain — and it, along with our other natural resources, must be optimized.

The end goal: to supply food that is affordable, nutritious and safe.

At the same time, farmers must be able to make a living, and farming must be done in a sustainable manner, shares U.S. Department of Agriculture Chief Economist Seth Meyer.

“We know that the footprint for U.S. cropland is not going to change much,” says USSEC’s Rosalind Leeck, Executive Director for Strategy and Market Access and Regional Director for Northeast Asia.

When you’re not expanding acres, how do you work to expand productivity?

Jeff Jorgenson, a U.S. Soy farmer from Iowa, says that paying attention to agronomics and understanding the crop’s needs are as important as they’ve ever been.

“There is nothing that is blanketed across any of my fields,” Jorgensen says.

Building on that, Lance Rezac, a U.S. Soy farmer from Kansas, shares:

“I farm some of the same ground that my grandfather farmed. He farmed with horses. They would put cloth and burlap around the tires to keep the mud from picking up — that was their technology. Nowadays, global positioning systems (GPS) have changed everything …

“It (GPS) knows exactly where every piece of equipment is and exactly what it’s applying. We’ve already been there and grid sampled that area, so as that tractor goes across the field we know what the seeding rate will be and how much chemistry will be applied. … Ten years ago, when we first planted using this technology, we saved 10% on our seed costs alone.”

The adoption of new technology and continued innovation of U.S. Soy farmers will lead to productivity gains and the supply of a high-quality, reliable and nutritious source of protein for food, feed and CPG companies worldwide. Last year, USDA Under Secretary for Trade and Foreign Agricultural Service, reported that U.S. Soy accounted for $41 million of total food and ag exports.

“Sustainably produced ag supplies remain a focus for producers and consumers around the world,” Taylor says.

This story was partially funded by U.S. Soy farmers, their checkoff and the soy value chain.

###