U.S. Soy farmers use precision ag to manage rising agricultural input costs.

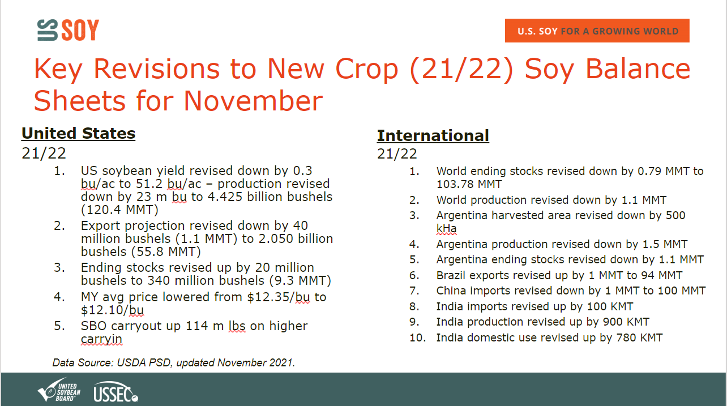

The U.S. Department of Agriculture released its November World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates report Nov. 9, revising U.S. soybean yield estimates down by .3 bushels per acre, bringing average U.S. soybean yields to 51.2 bushels per acre and the total crop to 120.4 million metric tons. Economists analyzed these numbers and more during the U.S. Soy WASDE Update, where farmers also shared their perspective from ground.

Both Mac Marshall, vice president of market intelligence for the U.S. Soybean Export Council and the United Soybean Board, and Kevin McNew, chief economist for Farmers Business Network, agreed the market was caught a little flat footed by the report, as soybean futured ticked up.

While U.S. ending stocks for soy were revised down, USDA bumped world ending stocks down by .79 MMT to 103.78 MMT.

Outside of these numbers, the elephant in the room for agricultural markets is what is happening with fertilizer and input costs, Marshall says.

In Brazil, for example, he says farmers are already talking about pulling back on inputs.

What impact might this have on the overall crop size?

“It’s been an astronomical year of price inflation not only for U.S. farmers but for farmers around the world,” McNew says. “We are seeing these massive price increases in fertilizer and major farm chemicals.

“We’ve seen glyphosate go from roughly $14 a gallon to $50 a gallon in a one-year time period. There will be really tough decisions for farmers coming into the 2022 growing season. The Brazilian farmers and Argentinian farmers are having to make those tough decisions now.”

McNew says based on his conversations, Brazilian farmers are more likely to spend on their soy crop and less likely to spend on that second season corn crop.

“The yield drag, or risk, most presents itself in that second season corn crop, which is already a gamble for them,” he says. “They are banking on that soy crop being really good.”

Marshall says that a smaller Brazilian corn crop will likely impact planting decisions by U.S. farmers come February and March, but just how much is to be determined.

In the northern hemisphere, McNew expects dramatic acreage shifts this year. He says winter wheat acres will be increase and that is a follow up to last year’s bump in acreage numbers.

“This year, I think we will see a dramatic cut in U.S. acres planted to corn and a big increase in acres planted to soybeans,” McNew says. “As a parallel, when we look at ‘like years,’ we have to go back to 2008 to see a massive run up in fertilizer prices like we have today.

“In 2008, we had $140 per barrel crude oil prices and natural gas doing crazy things like it is today. While crude and natural gas may not be at the levels of 2008, fertilizer prices are. In 2008, we saw wholesale changes in U.S. plantings: we lost 7 million acres of corn and gained over 10 million acres of soybeans with other crops shifting around as well.”

For farmers, Marshall says these dynamics materially change budget costs, as fertilizer prices are linked to energy prices and they get to those peak levels.

“This is potentially a really pivotal year as we head into 2022,” Marshall says, reminding there’s still a great deal that must happen between now and then.

Perspective From U.S. Soy Farmers

During the update, Jim Sutter, USSEC CEO, welcomed three U.S. soybean farmers to share their harvest conditions and progress, where they are on marketing the 2021 crop and their intentions as they look to 2022.

“Input costs are a big concern for us,” says Bill Bayliss, who farms near West Mansfield, Ohio, and serves as a director on the United Soybean Board and as a trustee on the Ohio Soybean Council. “At this time, we plan to plant more soybeans next year largely due to input costs.”

However, Bayliss says, they won’t change too much from their traditional rotation due to management practices and keeping that long-term goal of improving soil health with cover crops and no-till.

Kevin Mainord, who farms roughly 10,000 acres in southeast Missouri, shares the same sentiment, adding that “farmers will look to precision ag technologies to manage input costs and increase efficiency as much as possible.”

Further West, Clay Govier of Broken Bow, Nebraska, and secretary to the Nebraska Soybean Board, says that with the increased input costs, it’s even more important to tailor genetics to the location with an emphasis on yield and continuing to advance on-farm efficiency.

All three farmers have most of their 2021 crop marketed and have started marketing their 2022 crop.

Managing risk is the name of the game as the U.S. continues to produce a big crop with next year’s acreage numbers expected to be even bigger.

“I continue to be so impressed with U.S. farmers and how they adopt new technology and use the best practices,” Sutter says.

“… One of the challenges in this dynamic soy complex I hear customers facing right now is the shortage of synthetic amino acids, which is many times used in feed formulations. With the low cost of soybean meal and excellent amino acid composition, I encourage nutritionists and buyers to consider using soybean meal in feed formulations as a way to manage risk and supply. I believe there’s real value to be gained when you look to U.S. soybean meal as part of the formulation.”

The key takeaways: risk management is critical to business, and both farmers and economists see more soy planted in 2022 on higher input costs.

— Partially funded by U.S. Soybean Farmers and their checkoff